The Mauritanian Review: Tahar Rahim's compelling performance is inspired amid the mostly 'redacted' screenplay

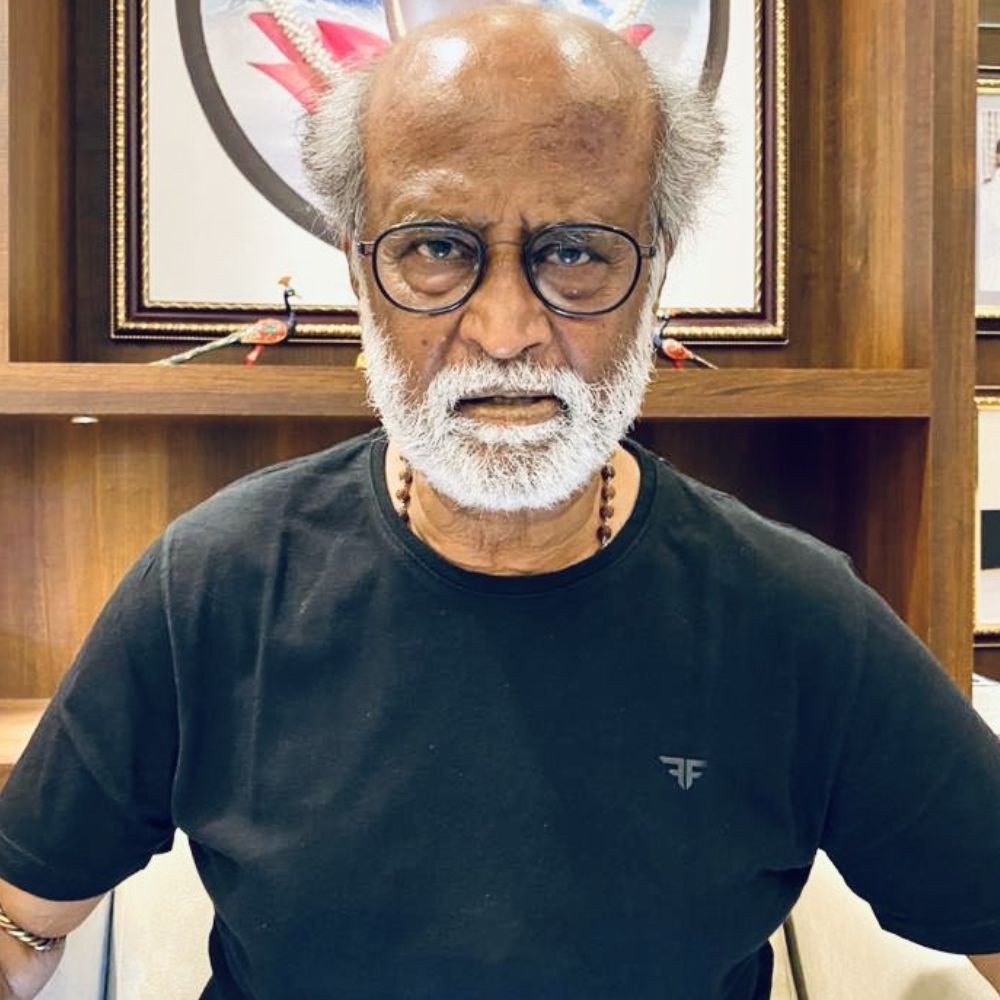

With an earnest ensemble performance, headlined by Tahar Rahim, Jodie Foster and Benedict Cumberbatch, The Mauritanian's 'safe' screenplay plays the spoilsport.

The Mauritanian

The Mauritanian Cast: Tahar Rahim, Jodie Foster, Benedict Cumberbatch, Shailene Woodley

The Mauritanian Director: Kevin Macdonald

The Mauritanian Stars: 3/5

The fact that the real-life Mohamedou Ould Slahi was incarcerated for fourteen years at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp without being charged for a crime should have been cinematic gold handed over on a silver platter to The Mauritanian director Kevin Macdonald. Add to that, we have an exceptional ensemble in Jodie Foster, Tahar Rahim, Benedict Cumberbatch and Shailene Woodley. What could go wrong? The mostly 'safe' screenplay!

Before we get into the specifics; for the unversed, The Mauritanian is based on the Mauritanian man Mohamedou Ould Slahi's gut-wrenching best-selling memoir Guantánamo Diary which traces Mohamedou's (Tahar Rahim) 14 years of unfair imprisonment. The circumstantial evidence points to Slahi as a key member involved in the 9/11 attacks with Nancy Hollander (Foster) and Teri Duncan (Woodley) taking up Mohamedou's habeas corpus case. Leading the prosecution is Lt. Colonel Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch) a God-loving noble military man, who promptly agrees to take the case as his close friend in the Marine Corps was killed during 9/11.

Over the course of two hours, we're engulfed in Slahi's intriguing story from his point of view, those on his side and to a certain extent, those opposing him. Intriguingly, both the defence and prosecution team go through the same motion of having their pre-conceived doubts before they come closer to the actual horrific truth. Referred to as 'Al Qaeda's Forrest Gump', the immediate onslaught of wanting to punish Mohamedou for a crime he may or may not have been involved in is burning bright in everyone; including Neil Buckland (Zachary Levi), who was a part of the "special projects" interrogation methods used against Slahi, except for Stuart, who finds the 'next to no evidence' against Mohamedou dicey.

Speaking of the "special projects" interrogation methods used, apart from the prior 'good cop' persuasion, the sequence emphasising the humiliating seventy-day torture Slahi had to endure (his mother being threatened, physical abuse, etc.), forced to give a false confession is spectacularly hurtful to watch. Alwin H. Küchler's cinematography and Justine Wright's editing along with Tom Hodge's music was especially tactful during this particular montage.

However, what's surprising is how Mohamedou is unlike how other falsely accused inmates would possibly behave if they were in his predicament. In fact, Slahi has a cheerful step even at the most claustrophobic of moments. You see that especially during the scenes where Mohamedou finds a companion in another inmate from Marseille, as he relays the importance of keeping the faith, even with the odds against them. You also see that in his spirited humour during the sessions with Nancy and Teri. While Hollander plays the atypical 'no shit' lawyer, Duncan is the good cop, who Slahi immediately gravitates towards the nurturing comfort of.

What's also different in this legal drama is how Couch isn't tainted as the bad guy and rather a good guy surrounded by bad guys. Even as you'd expect there to be animosity between Stuart and Nancy, it's never too over-the-top as we're used to seeing in such scenarios. However, the spunk is also what's lacking in The Mauritanian. The supposed 'bad guys' aren't clearly defined to leave a mark while the screenplay, which could have been phenomenal with the meaty source material it was adapted from, plays it extremely safe like I mentioned in the beginning.

The writing team, featuring M.B. Traven, Rory Haines and Sohrab Noshirvani could have created magic with the content fodder but somehow chose not to. Even the final courtroom sequence featuring a touching testimony from Mohamedou is anticlimatic and unlike other classic courtroom scenes like the iconic Jack Nicholson "You Can't Handle the Truth" moment from A Few Good Men. Although, some political statements were made, with George W. Bush's government being heavily criticised for Guantanamo Bay detention camp's harsh interrogation methods while the Obama administration got a textual mention for failing to close it. We also witness it when the documents highlighting Slahi's numerous interrogations were mostly redacted when sent to Hollander as opposed to when sent to Couch. None of the characters, except for Mohamedou are properly fleshed out to make them stand out in spite of earnest performances by both Jodie and Benedict, yes, even with the latter's thick Louisiana accent. Shailene was more or less a forgettable presence.

Tahar has marvellously portrayed the misunderstood personality of Slahi, which is especially proven in the final few moments showing us the real-life ever-smiling Mohamedou being embraced by his Mauritanian buddies after being released in 2016, singing a legendary Bob Dylan tune and showing his admiration for both Nancy and Teri with momentos. It's truly astonishing to see the cheerfulness imbibed in Slahi, after all the terror he's had to witness and that has been perfectly captured by Rahim with utmost grace.

The most emotionally stirring sequence comes at the beginning of the film, when Mohamedou has been called into questioning and tries to pacify his mom, telling her that he's going to come back soon. However, Slahi's mother knows in her heart that her beloved son, who just returned to Mauritania from Germany and was attending a wedding, was lying. It heartbreakingly turned out that Mohamedou never got to meet his mother, who sadly passed away years before he was released.

While Slahi's undying resilience was celebrated fruitfully in The Mauritanian, the writers chose to mostly redact the 'controversy' in the controversial real-life story. And, that's unfortunately where the movie misses its mark from being exceptional to mostly satisfying.

JOIN OUR WHATSAPP CHANNEL

JOIN OUR WHATSAPP CHANNEL