When Life Gives You Tangerines' popularity gets misused in China as IU-Park Bo Gum’s stills promoted illegally: Report

IU and Park Bo Gum's drama images were allegedly misused in a Chinese supermarket, sparking backlash over unauthorized image use and calls for stronger content protection. Read more here!

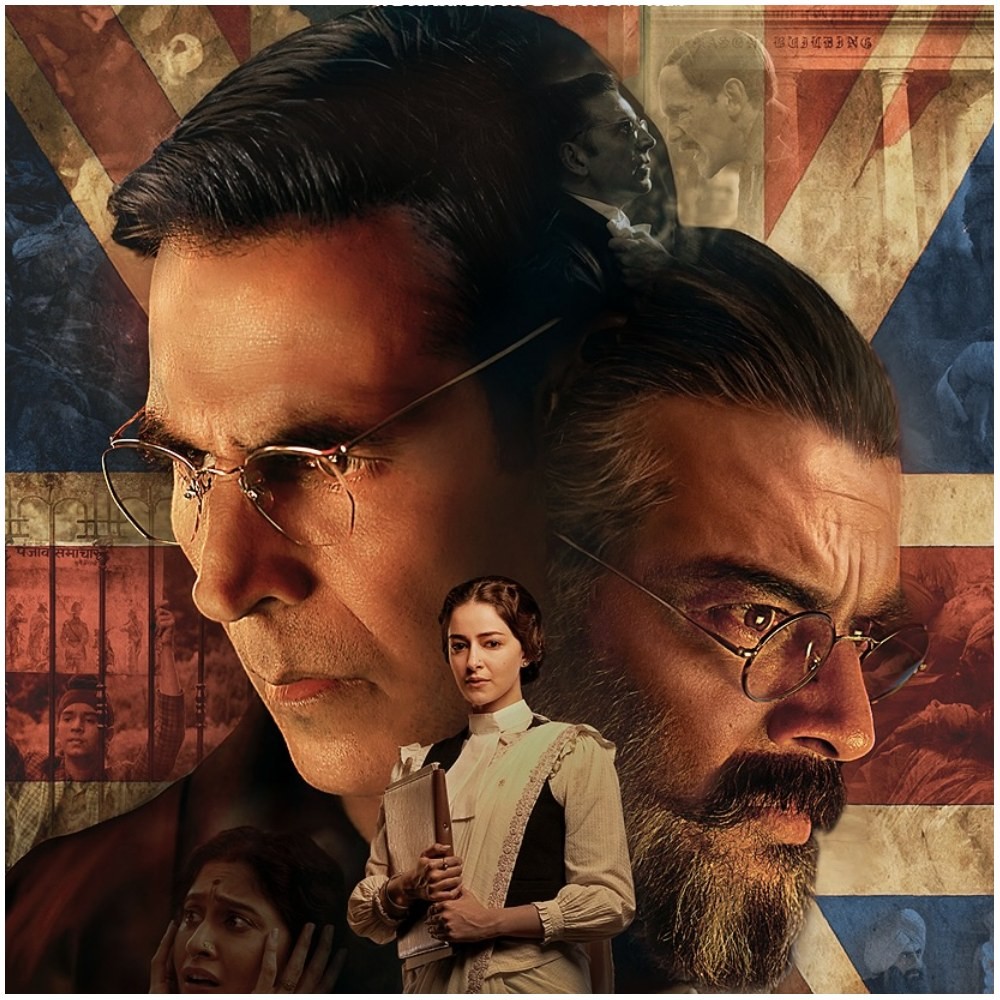

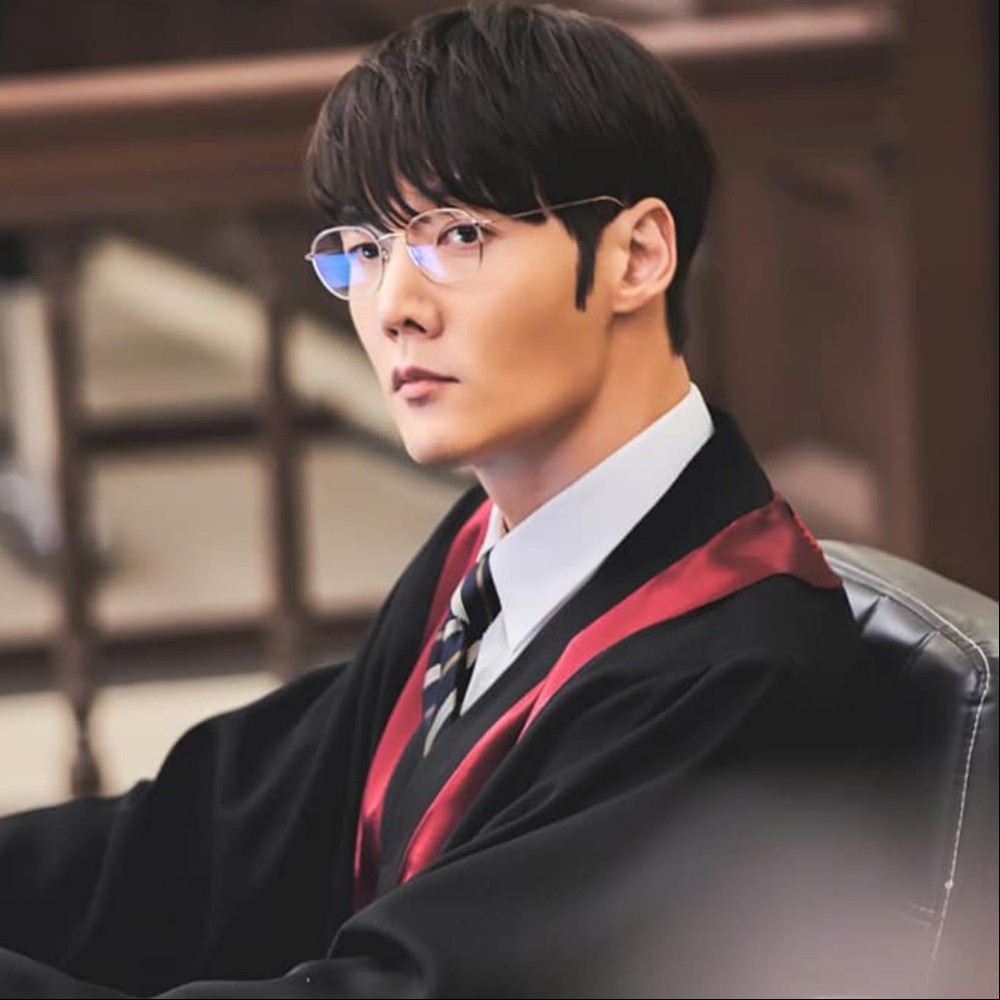

The hit Netflix series When Life Gives You Tangerines, starring popular actors Park Bo Gum and IU, has found itself at the center of a growing controversy after a supermarket in Hebei Province, China, was reportedly caught using the actors’ images without permission for commercial purposes. The unauthorized use of their likenesses has triggered widespread criticism and renewed concerns over intellectual property rights violations involving Korean content.

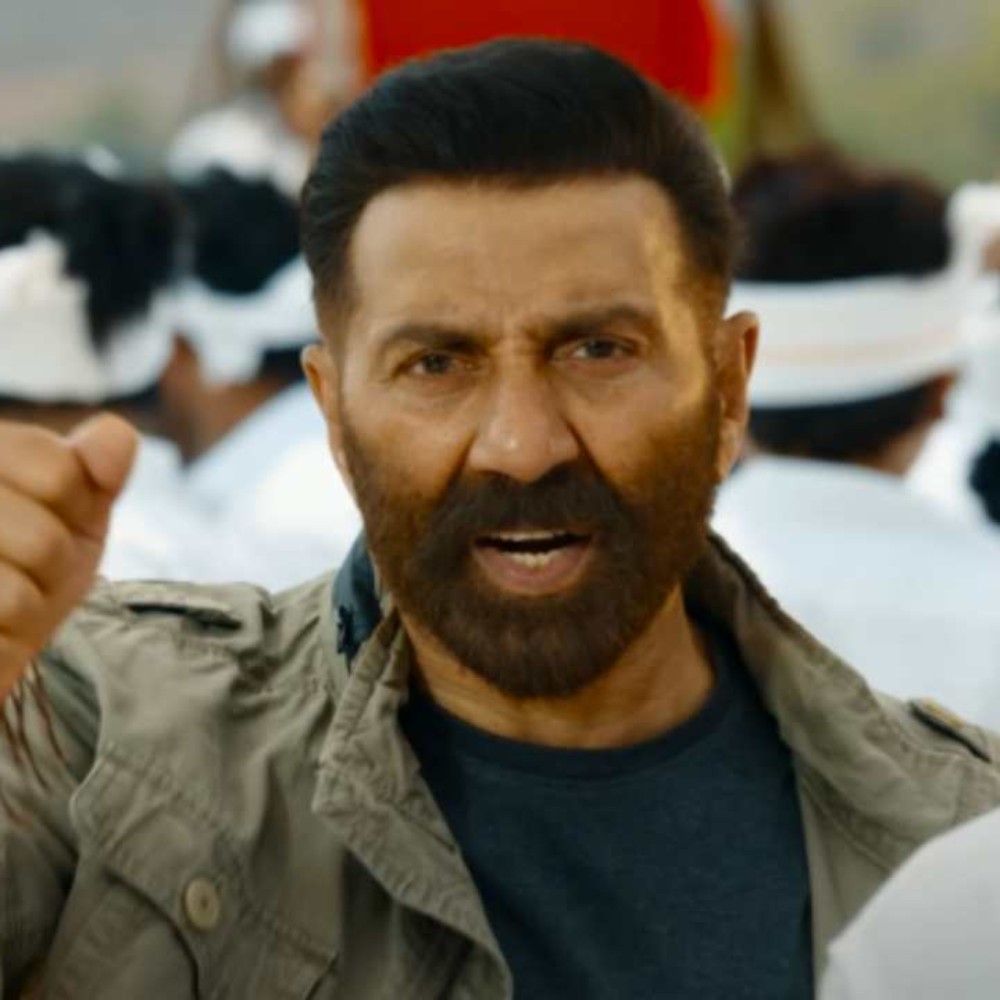

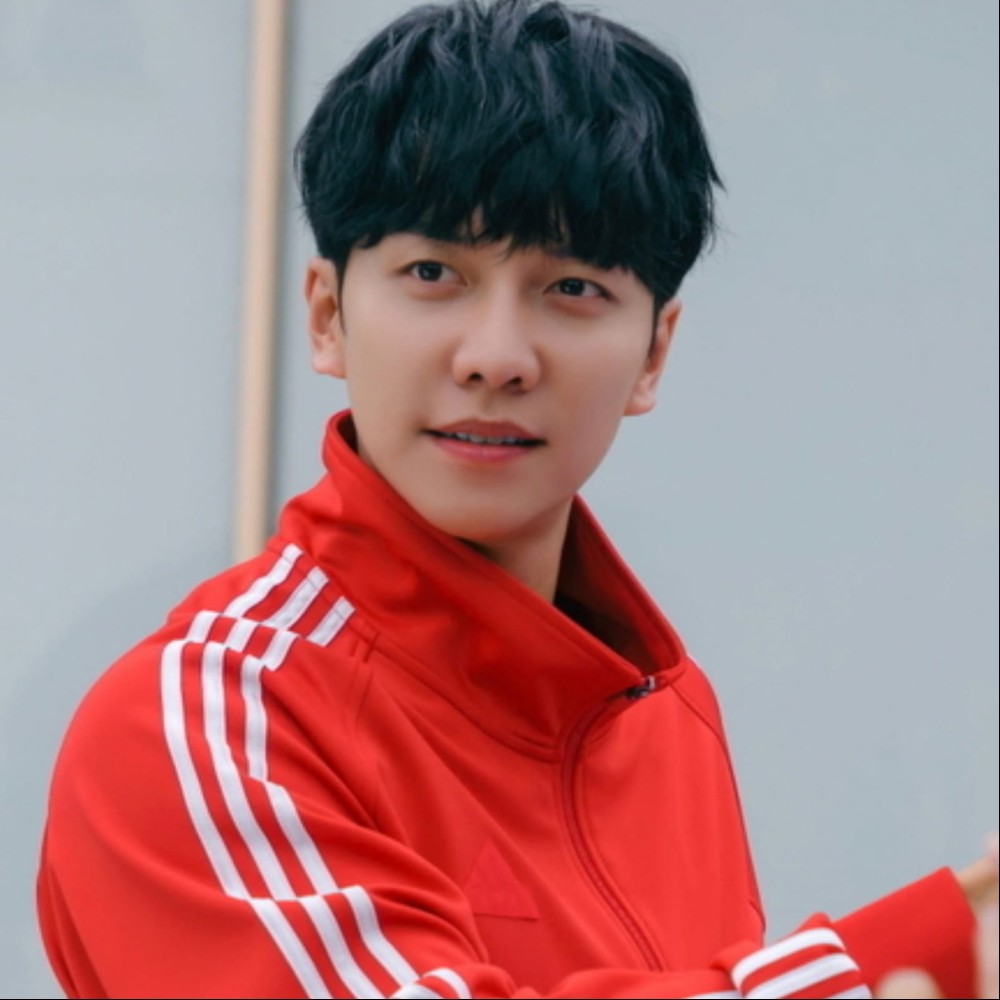

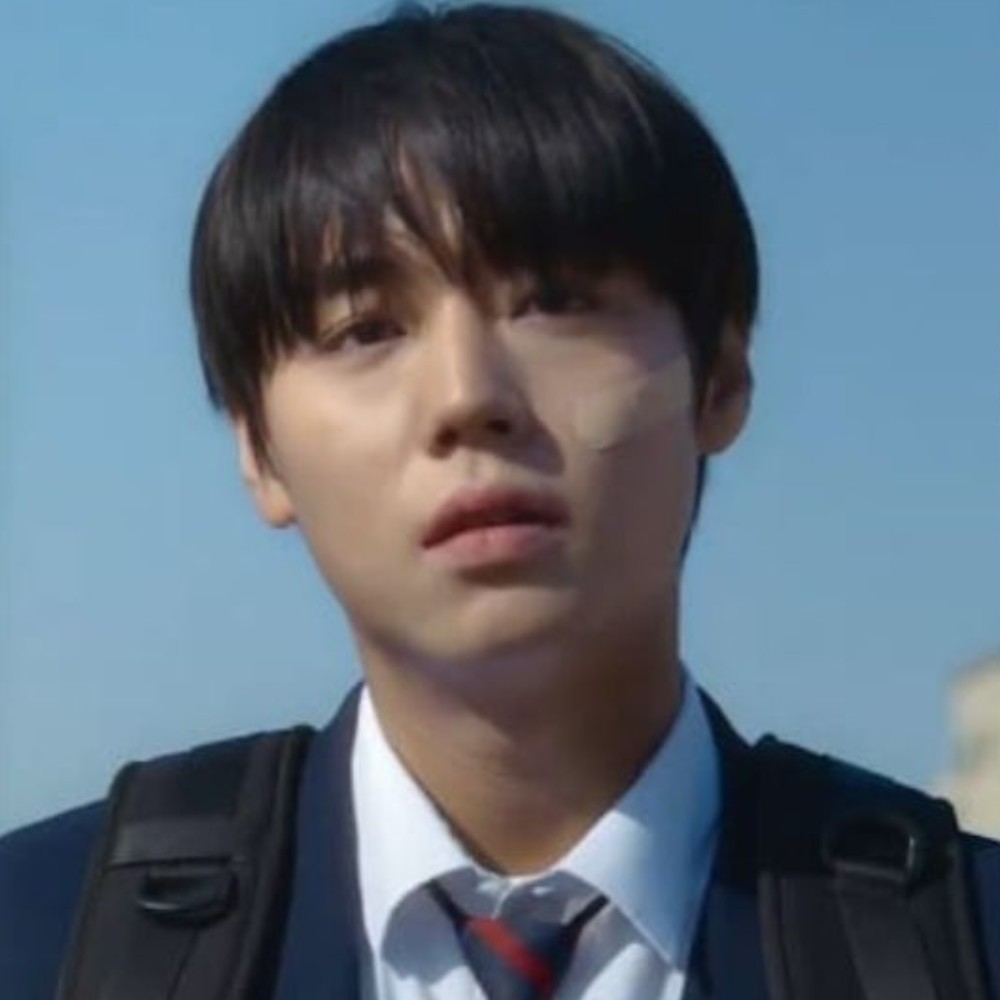

The issue came to light after Professor Seo Kyung Duk of Sungshin Women’s University received reports from concerned netizens. The reports revealed that a major supermarket in China was using stills from When Life Gives You Tangerines for promotional displays in various sections of the store. The images of Park Bo Gum (as Yang Gwan Shik) and IU (as Oh Ae Soon) appeared alongside product slogans such as “Sweet cabbage!” and “Try Ae Soon’s pea rice!”

The use of their images was done without any formal consent, raising serious questions about copyright infringement and commercial exploitation.

Professor Seo, an advocate for intellectual property rights, immediately voiced his disapproval, labeling the supermarket’s actions as an unlawful and unethical exploitation of the actors' images. “This is not just a case of illegal streaming but also blatant commercial exploitation of the actors’ images without consent,” he stated in a public statement. Seo further pointed out that this issue is not unique to When Life Gives You Tangerines.

He noted that Korean dramas, including global phenomena like Squid Game and The Glory, have been similarly misused in China to promote counterfeit goods, further fueling concerns over the illegal appropriation of Korean content for commercial gain.

While Netflix remains unavailable in China due to government restrictions, Korean dramas continue to circulate freely through unofficial and often illegal streaming channels. This phenomenon has exacerbated the issue of unauthorized usage, as the content becomes widely accessible to the public without proper licensing agreements. The Chinese supermarket’s blatant use of the actors’ images is seen as just one example of a much larger problem involving the unauthorized commercialization of Korean cultural products.

Professor Seo also raised concerns about the role of Chinese authorities in allowing such violations to occur. Seo stated, “If Chinese authorities are turning a blind eye to this, they’re effectively condoning the illegal distribution of foreign content. Government-level action is urgently needed to protect the rights of Korean creators and their intellectual property.”

For Korean creators and the entertainment industry, maintaining control over the distribution and commercial use of their work is becoming an ever more difficult task. As global audiences increasingly consume content through unofficial means, the need for stronger legal protections and enforcement mechanisms has never been more urgent.

JOIN OUR WHATSAPP CHANNEL

JOIN OUR WHATSAPP CHANNEL